Mutual information

In probability theory and information theory, the mutual information (sometimes known by the archaic term transinformation) of two random variables is a quantity that measures the mutual dependence of the two random variables. The most common unit of measurement of mutual information is the bit, when logarithms to the base 2 are used.

Contents |

Definition of mutual information

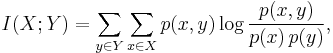

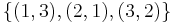

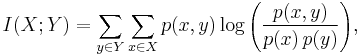

Formally, the mutual information of two discrete random variables X and Y can be defined as:

where p(x,y) is the joint probability distribution function of X and Y, and  and

and  are the marginal probability distribution functions of X and Y respectively.

are the marginal probability distribution functions of X and Y respectively.

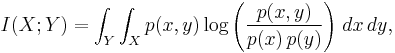

In the case of continuous random variables, the summation is matched with a definite double integral:

where p(x,y) is now the joint probability density function of X and Y, and  and

and  are the marginal probability density functions of X and Y respectively.

are the marginal probability density functions of X and Y respectively.

These definitions are ambiguous because the base of the log function is not specified. To disambiguate, the function I could be parameterized as I(X,Y,b) where b is the base. Alternatively, since the most common unit of measurement of mutual information is the bit, a base of 2 could be specified.

Intuitively, mutual information measures the information that X and Y share: it measures how much knowing one of these variables reduces uncertainty about the other. For example, if X and Y are independent, then knowing X does not give any information about Y and vice versa, so their mutual information is zero. At the other extreme, if X and Y are identical then all information conveyed by X is shared with Y: knowing X determines the value of Y and vice versa. As a result, in the case of identity the mutual information is the same as the uncertainty contained in Y (or X) alone, namely the entropy of Y (or X: clearly if X and Y are identical they have equal entropy).

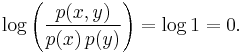

Mutual information quantifies the dependence between the joint distribution of X and Y and what the joint distribution would be if X and Y were independent. Mutual information is a measure of dependence in the following sense: I(X; Y) = 0 if and only if X and Y are independent random variables. This is easy to see in one direction: if X and Y are independent, then p(x,y) = p(x) p(y), and therefore:

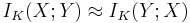

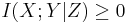

Moreover, mutual information is nonnegative (i.e. I(X;Y) ≥ 0; see below) and symmetric (i.e. I(X;Y) = I(Y;X)).

Relation to other quantities

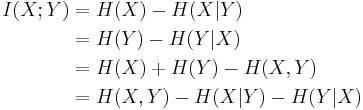

Mutual information can be equivalently expressed as

where H(X) and H(Y) are the marginal entropies, H(X|Y) and H(Y|X) are the conditional entropies, and H(X,Y) is the joint entropy of X and Y. Since H(X) ≥ H(X|Y), this characterization is consistent with the nonnegativity property stated above.

Intuitively, if entropy H(X) is regarded as a measure of uncertainty about a random variable, then H(X|Y) is a measure of what Y does not say about X. This is "the amount of uncertainty remaining about X after Y is known", and thus the right side of the first of these equalities can be read as "the amount of uncertainty in X, minus the amount of uncertainty in X which remains after Y is known", which is equivalent to "the amount of uncertainty in X which is removed by knowing Y". This corroborates the intuitive meaning of mutual information as the amount of information (that is, reduction in uncertainty) that knowing either variable provides about the other.

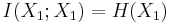

Note that in the discrete case H(X|X) = 0 and therefore H(X) = I(X;X). Thus I(X;X) ≥ I(X;Y), and one can formulate the basic principle that a variable contains at least as much information about itself as any other variable can provide.

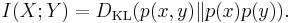

Mutual information can also be expressed as a Kullback-Leibler divergence, of the product p(x) × p(y) of the marginal distributions of the two random variables X and Y, from p(x,y) the random variables' joint distribution:

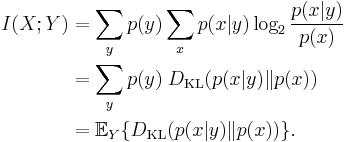

Furthermore, let p(x|y) = p(x, y) / p(y). Then

Thus mutual information can also be understood as the expectation of the Kullback-Leibler divergence of the univariate distribution p(x) of X from the conditional distribution p(x|y) of X given Y: the more different the distributions p(x|y) and p(x), the greater the information gain.

Variations of mutual information

Several variations on mutual information have been proposed to suit various needs. Among these are normalized variants and generalizations to more than two variables.

Metric

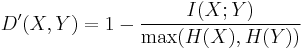

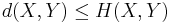

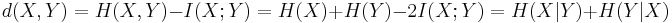

Many applications require a metric, that is, a distance measure between points. The quantity

satisfies the properties of a metric (triangle inequality, non-negativity, indiscernability and symmetry). This distance metric is also known as the Variation of information.

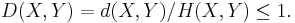

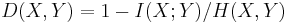

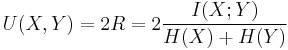

Since one has  , a natural normalized variant is

, a natural normalized variant is

The metric D is a universal metric, in that if any other distance measure places X and Y close-by, then the D will also judge them close.[1]

A set-theoretic interpretation of information (see the figure for Conditional entropy) shows that

which is effectively the Jaccard distance between X and Y.

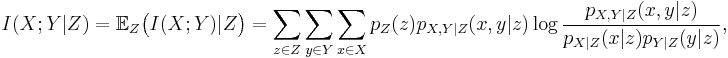

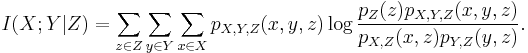

Conditional mutual information

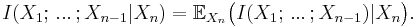

Sometimes it is useful to express the mutual information of two random variables conditioned on a third.

which can be simplified as

Conditioning on a third random variable may either increase or decrease the mutual information, but it is always true that

for discrete, jointly distributed random variables X, Y, Z. This result has been used as a basic building block for proving other inequalities in information theory.

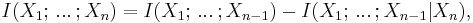

Multivariate mutual information

Several generalizations of mutual information to more than two random variables have been proposed, such as total correlation and interaction information. If Shannon entropy is viewed as a signed measure in the context of information diagrams, as explained in the article Information theory and measure theory, then the only definition of multivariate mutual information that makes sense is as follows:

and for

where (as above) we define

(This definition of multivariate mutual information is identical to that of interaction information except for a change in sign when the number of random variables is odd.)

Applications

Applying information diagrams blindly to derive the above definition has been criticised, and indeed it has found rather limited practical application, since it is difficult to visualize or grasp the significance of this quantity for a large number of random variables. It can be zero, positive, or negative for any

One high-dimensional generalization scheme which maximizes the mutual information between the joint distribution and other target variables is found to be useful in feature selection.[2]

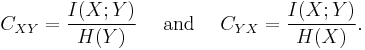

Normalized variants

Normalized variants of the mutual information are provided by the coefficients of constraint (Coombs, Dawes and Tversky 1970) or uncertainty coefficient (Press & Flannery 1988)

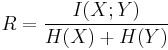

The two coefficients are not necessarily equal. A more useful and symmetric scaled information measure is the redundancy

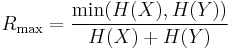

which attains a minimum of zero when the variables are independent and a maximum value of

when one variable becomes completely redundant with the knowledge of the other. See also Redundancy (information theory). Another symmetrical measure is the symmetric uncertainty (Witten & Frank 2005), given by

which represents a weighted average of the two uncertainty coefficients (Press & Flannery 1988).

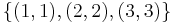

If we consider mutual information as a special case of the total correlation or dual total correlation, the normalized versions are respectively,

![\frac{I(X;Y)}{\min\left[ H(X),H(Y)\right]}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2cc14561e8fc4bd339267d9f270e08e1.png) and

and

Other normalized versions are provided by the following expressions (Yao 2003, Strehl & Ghosh 2002).

The quantity

is a metric, i.e. satisfies the triangle inequality, etc. The metric  is also a universal metric.[3]

is also a universal metric.[3]

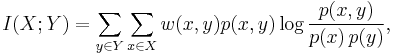

Weighted variants

In the traditional formulation of the mutual information,

each event or object specified by  is weighted by the corresponding probability

is weighted by the corresponding probability  . This assumes that all objects or events are equivalent apart from their probability of occurrence. However, in some applications it may be the case that certain objects or events are more significant than others, or that certain patterns of association are more semantically important than others.

. This assumes that all objects or events are equivalent apart from their probability of occurrence. However, in some applications it may be the case that certain objects or events are more significant than others, or that certain patterns of association are more semantically important than others.

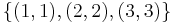

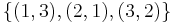

For example, the deterministic mapping  may be viewed as stronger than the deterministic mapping

may be viewed as stronger than the deterministic mapping  , although these relationships would yield the same mutual information. This is because the mutual information is not sensitive at all to any inherent ordering in the variable values (Cronbach 1954, Coombs & Dawes 1970, Lockhead 1970), and is therefore not sensitive at all to the form of the relational mapping between the associated variables. If it is desired that the former relation — showing agreement on all variable values — be judged stronger than the later relation, then it is possible to use the following weighted mutual information (Guiasu 1977)

, although these relationships would yield the same mutual information. This is because the mutual information is not sensitive at all to any inherent ordering in the variable values (Cronbach 1954, Coombs & Dawes 1970, Lockhead 1970), and is therefore not sensitive at all to the form of the relational mapping between the associated variables. If it is desired that the former relation — showing agreement on all variable values — be judged stronger than the later relation, then it is possible to use the following weighted mutual information (Guiasu 1977)

which places a weight  on the probability of each variable value co-occurrence,

on the probability of each variable value co-occurrence,  . This allows that certain probabilities may carry more or less significance than others, thereby allowing the quantification of relevant holistic or prägnanz factors. In the above example, using larger relative weights for

. This allows that certain probabilities may carry more or less significance than others, thereby allowing the quantification of relevant holistic or prägnanz factors. In the above example, using larger relative weights for  ,

,  , and

, and  would have the effect of assessing greater informativeness for the relation

would have the effect of assessing greater informativeness for the relation  than for the relation

than for the relation  , which may be desirable in some cases of pattern recognition, and the like. There has been little mathematical work done on the weighted mutual information and its properties, however.

, which may be desirable in some cases of pattern recognition, and the like. There has been little mathematical work done on the weighted mutual information and its properties, however.

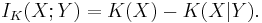

Absolute mutual information

Using the ideas of Kolmogorov complexity, one can consider the mutual information of two sequences independent of any probability distribution:

To establish that this quantity is symmetric up to a logarithmic factor ( ) requires the chain rule for Kolmogorov complexity (Li 1997). Approximations of this quantity via compression can be used to define a distance measure to perform a hierarchical clustering of sequences without having any domain knowledge of the sequences (Cilibrasi 2005).

) requires the chain rule for Kolmogorov complexity (Li 1997). Approximations of this quantity via compression can be used to define a distance measure to perform a hierarchical clustering of sequences without having any domain knowledge of the sequences (Cilibrasi 2005).

Applications of mutual information

In many applications, one wants to maximize mutual information (thus increasing dependencies), which is often equivalent to minimizing conditional entropy. Examples include:

- In telecommunications, the channel capacity is equal to the mutual information, maximized over all input distributions.

- Discriminative training procedures for hidden Markov models have been proposed based on the maximum mutual information (MMI) criterion.

- RNA secondary structure prediction from a multiple sequence alignment.

- Phylogenetic profiling prediction from pairwise present and disappearance of functionally link genes.

- Mutual information has been used as a criterion for feature selection and feature transformations in machine learning. It can be used to characterize both the relevance and redundancy of variables, such as the minimum redundancy feature selection.

- Mutual information is often used as a significance function for the computation of collocations in corpus linguistics.

- Mutual information is used in medical imaging for image registration. Given a reference image (for example, a brain scan), and a second image which needs to be put into the same coordinate system as the reference image, this image is deformed until the mutual information between it and the reference image is maximized.

- Detection of phase synchronization in time series analysis

- In the infomax method for neural-net and other machine learning, including the infomax-based Independent component analysis algorithm

- Average mutual information in delay embedding theorem is used for determining the embedding delay parameter.

- Mutual information between genes in expression microarray data is used by the ARACNE algorithm for reconstruction of gene networks.

- In statistical mechanics, Loschmidt's paradox may be expressed in terms of mutual information.[4][5] Loschmidt noted that it must be impossible to determine a physical law which lacks time reversal symmetry (e.g. the second law of thermodynamics) only from physical laws which have this symmetry. He pointed out that the H-theorem of Boltzmann made the assumption that the velocities of particles in a gas were permanently uncorrelated, which removed the time symmetry inherent in the H-theorem. It can be shown that if a system is described by a probability density in phase space, then Liouville's theorem implies that the joint information (negative of the joint entropy) of the distribution remains constant in time. The joint information is equal to the mutual information plus the sum of all the marginal information (negative of the marginal entropies) for each particle coordinate. Boltzmann's assumption amounts to ignoring the mutual information in the calculation of entropy, which yields the thermodynamic entropy (divided by Boltzmann's constant).

- The mutual information is used to learn the structure of Bayesian networks/dynamic Bayesian networks, which explain the causal relationship between random variables, as exemplified by the GlobalMIT toolkit [1]: learning the globally optimal dynamic Bayesian network with the Mutual Information Test criterion.

See also

Notes

- ^ Alexander Kraskov, Harald Stögbauer, Ralph G. Andrzejak, and Peter Grassberger, "Hierarchical Clustering Based on Mutual Information", (2003) ArXiv q-bio/0311039

- ^ Christopher D. Manning, Prabhakar Raghavan, Hinrich Schütze (2008). An Introduction to Information Retrieval. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521865719.

- ^ Kraskov, et al. ibid.

- ^ Hugh Everett Theory of the Universal Wavefunction, Thesis, Princeton University, (1956, 1973), pp 1–140 (page 30)

- ^ Hugh Everett, Relative State Formulation of Quantum Mechanics, Reviews of Modern Physics vol 29, (1957) pp 454–462.

References

- Cilibrasi, R.; Paul Vitányi (2005). "Clustering by compression" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 51 (4): 1523–1545. doi:10.1109/TIT.2005.844059. http://www.cwi.nl/~paulv/papers/cluster.pdf.

- Coombs, C. H., Dawes, R. M. & Tversky, A. (1970), Mathematical Psychology: An Elementary Introduction, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

- Cronbach L. J. (1954). On the non-rational application of information measures in psychology, in H Quastler, ed., Information Theory in Psychology: Problems and Methods, Free Press, Glencoe, Illinois, pp. 14–30.

- Kenneth Ward Church and Patrick Hanks. Word association norms, mutual information, and lexicography, Proceedings of the 27th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 1989.

- Guiasu, Silviu (1977), Information Theory with Applications, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Li, Ming; Paul Vitányi (February 1997). An introduction to Kolmogorov complexity and its applications. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0387948686.

- Lockhead G. R. (1970). Identification and the form of multidimensional discrimination space, Journal of Experimental Psychology 85(1), 1–10.

- Athanasios Papoulis. Probability, Random Variables, and Stochastic Processes, second edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1984. (See Chapter 15.)

- Press, WH; Teukolsky, SA; Vetterling, WT; Flannery, BP (2007). "Section 14.7.3. Conditional Entropy and Mutual Information". Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8. http://apps.nrbook.com/empanel/index.html#pg=758

- Strehl, Alexander; Joydeep Ghosh (2002). "Cluster ensembles – a knowledge reuse framework for combining multiple partitions" (PDF). Journal of Machine Learning Research 3: 583–617. doi:10.1162/153244303321897735. http://strehl.com/download/strehl-jmlr02.pdf.

- Witten, Ian H. & Frank, Eibe (2005), Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques, Morgan Kaufmann, Amsterdam.

- Yao, Y. Y. (2003) Information-theoretic measures for knowledge discovery and data mining, in Entropy Measures, Maximum Entropy Principle and Emerging Applications, Karmeshu (ed.), Springer, pp. 115–136.

- Peng, H.C., Long, F., and Ding, C., "Feature selection based on mutual information: criteria of max-dependency, max-relevance, and min-redundancy," IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, Vol. 27, No. 8, pp. 1226–1238, 2005. Program

- Andre S. Ribeiro, Stuart A. Kauffman, Jason Lloyd-Price, Bjorn Samuelsson, and Joshua Socolar, (2008) "Mutual Information in Random Boolean models of regulatory networks", Physical Review E, Vol.77, No.1. arXiv:0707.3642.

- Wells, W.M. III; Viola, P., Atsumi, H., Nakajima, S., Kikinis, R. (1996). "Multi-modal volume registration by maximization of mutual information" (PDF). Medical Image Analysis 1 (1): 35–51. doi:10.1016/S1361-8415(01)80004-9. PMID 9873920. http://www.ai.mit.edu/people/sw/papers/mia.pdf.

![\frac{I(X;Y)}{\min\left[ H(X),H(Y)\right]}, ~~~~~~~ \frac{I(X;Y)}{H(X,Y)}, ~~~~~~~ \frac{I(X;Y)}{\sqrt{H(X)H(Y)}}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/97132e1f7b6d489aa97a77946b0ae8a2.png)